Do Ostrom’s rules for governing the commons scale up?

On the uses and mis-uses of extending Ostrom's rules to the provision of global public goods

In this inaugural post, I want to examine the scalability of Ostrom’s design principles for the governance of common-pool resources (CPR). While Ostrom’s principles or rules are not merely of local importance, I claim, there are global public goods problems for which they are ill-suited. Specifically, I will argue that Ostrom’s principles can be scaled up when dealing with the provision of weakest-link global public goods (GPG), whereas they are not conducive to providing aggregate-effort GPGs.

Prisoners no longer? Ostrom’s rules and the successful governance of local CPRs

By way of preamble, note that public goods are both non-excludable and non-rivalrous in use, whereas CPRs are non-excludable but rivalrous. Accordingly, no one can be excluded from consuming public goods, and consumption by any one person does not reduce the amount others can consume. Similarly, CPRs are non-excludable, with rivalry in consumption implying that the amount any person can consume is a decreasing function of others’ consumption (Ostrom 2005, 25).

It is useful, I think, to briefly outline Hardin’s tragedy of the commons since the latter provided the impetus for the formulation of Ostrom’s design principles. Hardin’s (1968) parable, outlined in “The Tragedy of the Commons”, starts with a CPR, namely a pasture, and relies on three assumptions. (1) Given non-excludability, every herdsman can use the pasture to let his cattle graze. (2) Each herdsman’s payoff is an increasing function of the number of his cattle on the pasture. (3) Rivalry entails that every herdsman’s payoff is a decreasing function of the number of other herdsmen’s cattle. Hardin then concludes that tragedy ensues because ‘[e]ach men is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit in a world that is limited.’ (Hardin 1968, 1244) Thus, the tragedy of the commons resides in the pursuit of self-interest by everyone, yielding a collectively suboptimal outcome - the destruction of the pasture.

This parable’s game-theoretic structure is that of a symmetric, one-shot, N-person prisoner’s dilemma, which, following Barrett (2016), has three features. (1) Every player’s dominant strategy consists in ‘defection’, which can here be interpreted as adding cattle to the pasture, with ‘cooperation’ implying the opposite. Accordingly, all players derive a strictly higher profit from ‘defection’ than from ‘cooperation’. (2) Under certain assumptions,1 there exists a unique pure-strategy Nash equilibrium (PSNE), with all players choosing ‘defection’, i.e. the unique (N*1)-vector of strategies that maximises each player’s profit, given other players’ best responses, requires all players to defect. (3) The PSNE is not Pareto-optimal since all players would be better off if they played ‘cooperation’, thereby avoiding the destruction of the pasture.

To preempt any terminological confusion between CPRs and public goods, note that arguments about CPRs can be interpreted from a public goods perspective. This follows from observing that the sustainable use of a CPR, such as a pasture, is itself a public good. Given the latter’s non-excludability and non-rivalry, each herdsman can reap the benefit of a sustainable pasture without incurring the costs of contributing to its provision. This free-rider behaviour characterises the PSNE, with the upshot being that the public good will not be provided. This implies that the destruction of a CPR is equivalent to the failure to provide the public good of a sustainable CPR. Hence, Hardin’s tragedy, though initially applied to CPRs, also holds for public goods, a point that will become relevant in our discussion of the provision of aggregate-effort public goods.

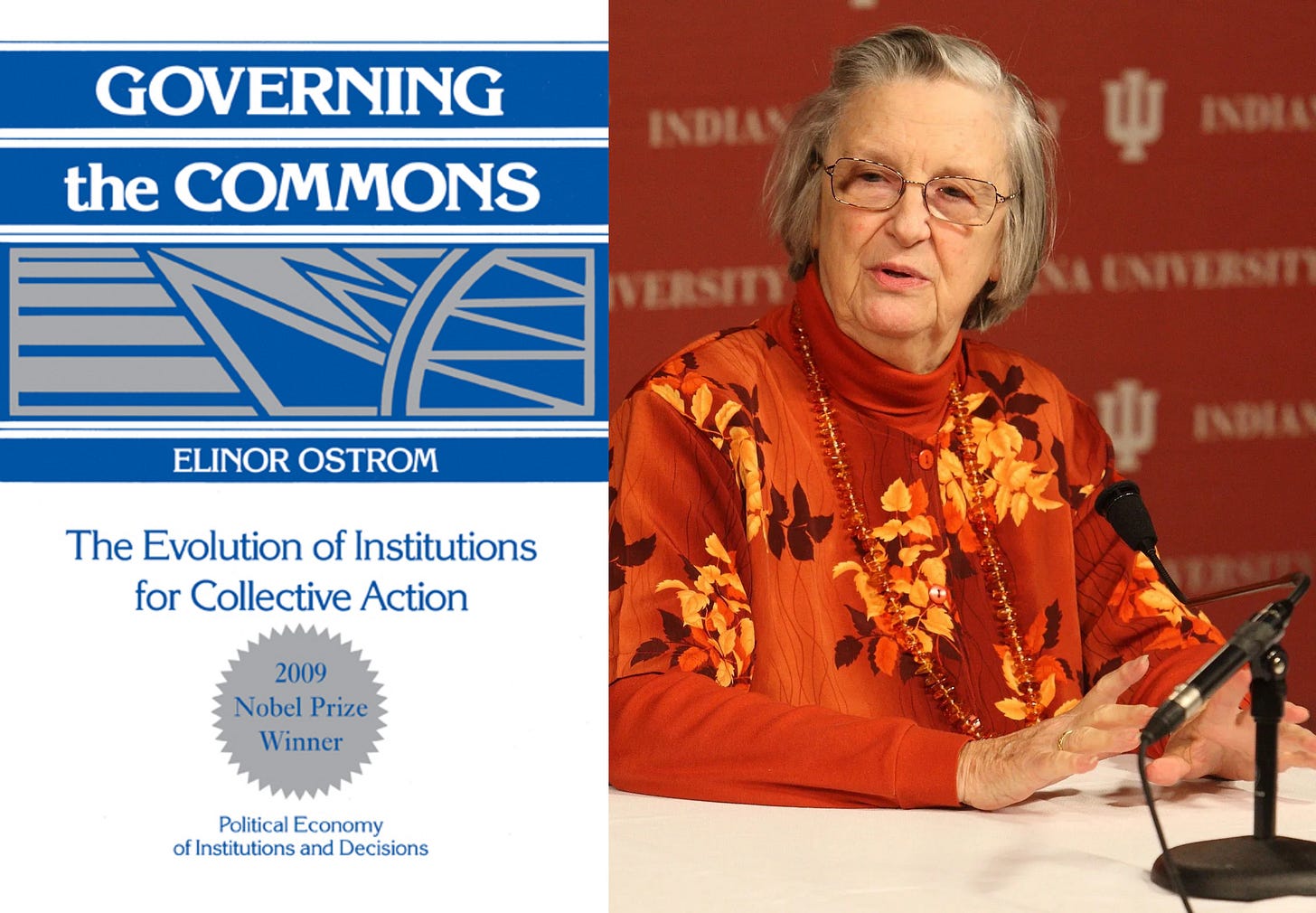

The tragedy of the commons seems to predict that public goods are bound to be underprovided and CPRs overused. Ostrom, however, showed that this prediction is at odds with the fact that CPRs are often successfully provided, especially locally. This led her to argue that, though some collective action problems are Prisoner’s dilemmata, many are not (Bueno de Mesquita 2016, 136). In Governing the Commons, Ostrom draws on case studies to, inductively, formulate design principles for the provision of CPRs - essential conditions which successful governance systems for CPRs have exhibited (Ostrom 2015, 90). There are eight such design principles:

1. Clearly defined boundaries

2. Proportional equivalence between benefits and costs2

3. Collective-choice arrangements

4. Monitoring

5. Graduated sanctions

6. Conflict-resolution mechanisms

7. Minimal recognition of rights to organise

8. Nested enterprises

The first principle requires that the boundary between the CPR and the surrounding environment, as well as the distinction between users and non-users, is clearly specified. The second principle holds that the ‘contribution expected of an individual is in some way related to the benefits they derive from the collective good.’ (Hindmoor and Taylor 2015, 159). There should be a voice mechanism, the third principle says, which allows CPR-users to modify operational rules – the rules governing the use of the CPR (Ostrom 2015, 93).

The fourth and fifth principle constitute the ‘conceptual core’ (McGinnis and Ostrom 2008, 205) of the design principles. The former necessitates that some or all of the users of a CPR should monitor other users’ compliance with the operational rules for using that CPR and that the monitors must be accountable to all other users. The latter principle holds that violations of the operational rules are to be punished in a gradual manner, in accordance with the severity of the transgression. Finally, the last three principles imply that there must be low-cost ways of resolving conflicts, that external authorities must grant CPR-users the right to set their own operational rules, and that for large-scale CPRs governance should be organised in multiple layers.

Let us focus on the two core principles - principles four and five - to see how they can solve or alleviate the free-rider problem when dealing with the sustainable provision of local CPRs. Ostrom (2015, 45) argues that, owing to monitoring and graduated sanctions, conditional cooperation can emerge, thus disincentivising free-riding and making collective action possible. Such conditional cooperation requires that (a) users believe a set of operational rules to be effective in generating higher benefits than the benefits derived in their absence and (b) mutual monitoring is exercised – possibly via norms (Ostrom, Walker, and Gardner 1992) - to reassure each user that violations of operational rules will be sanctioned, albeit in a gradual manner. If (a) and (b) obtain, users commit themselves to using the CPR sustainably, provided that all others do so too and that free-riders are punished. This type of ‘contingent self-commitment’ (Ostrom 2015, 100) allows CPR users, at least sometimes, to solve the free-rider problem without intervention by an external authority.3

The problem of scale

Whilst Ostrom’s design principles imply that conditional cooperation can emerge locally, one might, following Ostrom et al. (1999), wonder whether the design principles can help us solve free-rider problems on a global scale. Addressing the latter amounts to finding ways of providing global public goods (GPG), goods that are non-excludable, non-rivalrous and whose costs and benefits extend across territorial boundaries (Barrett 2007).

Weakest-link public goods and Ostrom’s rules

Following Hirshleifer (1983, 374) and Barrett (2007, 48), GPGs are said to have a weakest-link structure if their provision requires that all players’ profit-maximising contributions to the GPG are equal to or above some minimum threshold value. The following scenario illustrates the problem of providing a weakest-link GPGs. Suppose that the GPG to be provided is the eradication of an endemic disease, such as smallpox. Countries, assume, are to choose the level of vaccination coverage of the population, namely the share of the population that is vaccinated.

It is known by all countries that there is a critical threshold of vaccination coverage, i.e. the minimum fraction of the population that has to be vaccinated for the disease to be eradicated. In those countries that choose a vaccination level below the critical threshold the disease will remain endemic but controllable; whereas those countries with vaccination coverage exceeding the critical threshold will eradicate the disease. Countries’ payoffs are higher in a world where the public good is provided - as opposed to a world in which the disease remains endemic.

Will the disease be eradicated? The answer depends on whether or not the lowest level of vaccination coverage chosen by any country exceeds the critical threshold. No country wants to eliminate the disease as long as the vaccination level of even one country is below the critical threshold. In that case, the disease could spread, even to those countries whose vaccination level exceeds the critical threshold, thereby undermining their efforts to achieve immunity. Hence, the presence of even one country with vaccination coverage below the threshold suffices for other countries not to vaccinate a high enough fraction of their populations so that the disease will be eradicated.

This country can then be said to represent the weakest link in that it is pivotal in providing the GPG. That is, the GPG will be provided if the vaccination coverage of the weakest link exceeds the critical threshold and vice versa. Therefore, the eradication of the disease is a coordination problem, requiring countries to coordinate on one of two possible PSNE: a world in which the disease remains both endemic and controllable or one in which it is wholly eradicated. Which PSNE will be selected depends on the weakest link, the country with the lowest level of vaccination coverage.

Weakest-link-type provision problems therefore have four features. (1) Countries do not have dominant strategies: it is not always better for a given country to either vaccinate a fraction of the population below or above the threshold. (2) The existence of two PSNEs makes this game a coordination problem, with players coordinating on the choice of one PSNE. (3) One PSNE is Pareto-optimal since no country's position can be improved in a world where the disease is eradicated. (4) Increasing the number of players in weakest-link games does not necessarily imply that the solution to the coordination problem or the PSNE will change. In the above scenario, the addition of a new country will only change the PSNE if, in contrast to all other countries, its vaccination coverage is below the critical threshold.

Why then can Ostrom’s principles be scaled up to further the provision of weakest-link GPGs? The answer lies in the observation that, given the pivotality of the weakest link in providing the GPG, the Pareto-optimal outcome to the coordination problem can (sometimes) be achieved by employing Ostrom’s principles to help the weakest link exceed the critical threshold.

This can be seen by considering the successful eradication of smallpox in the late 1970s (Dattani 2020). As Henderson (1987) and Barrett (2016) note, the world’s triumph over smallpox was the result of a WHO-led effort that began in 1967. In 1977, the last case of smallpox was reported in Somalia. Had smallpox become endemic in Somalia, it would have likely spread to other countries, eventually leading countries to coordinate on the Pareto-inferior PSNE. But the Somalian government, in cooperation with WHO personnel, engaged in aggressive contact-tracing and put local community leaders in charge of monitoring and sanctioning compliance with hygiene rules (Henderson 1987). That is, the Somalian authorities implemented Ostrom’s two core principles – monitoring and sanctioning.

The success in eradicating smallpox implies that Ostrom’s principles can be scaled up, when dealing with weakest-link GPGs, for two reasons. First, the weakest-link country’s pivotality in providing the GPG means that a global problem acquires a local dimension. For the globally Pareto-optimal PSNE to be achieved, it is sufficient to ensure that, locally, the weakest link contributes above the critical threshold. Second, Ostrom’s design principles can then be deployed to induce conditional cooperation in the weakest-link country, thereby preserving or establishing the Pareto-optimal PSNE.

Aggregate-effort public goods and Ostrom’s rules

Let us now turn to the limits of scaling up Ostrom’s design principles by analysing GPGs that have an aggregate-effort structure. The provision of aggregate-effort GPGs depends on the sum total of all players’ contributions. The most prominent example of such a GPG is climate change mitigation, viz. policies to reduce the concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, since the extent to which greenhouse gas emissions are reduced depends on the sum of all countries’ emissions reductions (Barrett 2007, 74).

The game-theoretic structure of providing these GPGs is that of the above N-person prisoner’s dilemma. As such, the above three features of the prisoner’s dilemma hold. Importantly, however, a fourth feature becomes particularly important on the global stage. As the number of players increases, the incentive to free-ride increases if the per-country benefits implied by the higher aggregate effort are lower than the per-country costs of contributing to the GPG. So, as the number of players increases, the contribution levels implied by the PSNE diverge further from the Pareto-optimal level of contributions.

To see this, consider the role of countries A and B when providing climate change mitigation, where country A has a large population and produces high emissions, whereas country B is significantly smaller in these respects. Now country C, which is smaller than country A but bigger than country B, starts to engage in mitigation. Since the aggregate effort has increased, more mitigation is provided and all countries derive higher benefits, though the per-country benefits differ in accordance with the countries’ size.

Were B to cease to mitigate, the aggregate amount of mitigation provided would not be substantially reduced, which would not be true for country A. B can therefore reap most of the benefits of mitigation without incurring the costs of its provision. As a result, the addition of another player – country C - has increased B’s incentive to free-ride. If B free-rides, country C will only continue contributing if its fraction of the total benefits is higher than the costs of provision. Otherwise, it will free ride too, leading to the PSNE of ‘all defect’, with no mitigation being provided.4

The preceding shows that, when GPGs have an aggregate-effort structure, Hardin’s tragedy is likely to rear its uncooperative head again. Two features of the international political economy of GPG provision compound this problem: unanimity and voluntarism. Unanimity is the prevailing collective-choice arrangement in the global arena (Barrett 2016). The latter implies that it is rare for sanctions, particularly in the form of tariffs (Keohane and Oppenheimer 2016), to be enshrined in international agreements. After all, countries seeking to avoid these sanctions would either not ratify these agreements or withdraw5 from them once the sanctioning mechanisms start to “bite”. The 2015 Paris Agreement’s Pledge-and-Review system illustrates the idea of voluntarism, with countries voluntarily specifying the amount of emissions reductions they intend to achieve (nationally determined contributions) and committing themselves to having their progress reviewed (Keohane and Oppenheimer 2016).

Such a system would be useful in ensuring conditional cooperation, as envisaged by Ostrom, if countries could be incentivised to not withdraw from agreements. Unanimity can, however, thwart the use of effective sanctions in international treaties, entailing that the voluntaristic Pledge-and-Review system might not sufficiently increase the costs of reneging on voluntary contributions for the reasons set out in the previous paragraph. As a result, unanimity can sometimes undermine voluntarism.6 Since Ostrom’s principles do not provide much guidance for creating incentives to not withdraw – despite their critical role in the provision of aggregate-effort GPGs – her principles fail to scale up when providing GPGs that hinge on the sum of all countries’ contributions.

Conclusion

I have argued that Ostrom’s design principles for the governance of CPRs are not merely of local importance. Both the discussion of the game-theoretic features of the tragedy of the commons and Ostrom’s principles showed the latter’s relevance to reside in the fact that they furnish us with an escape route from Hardin’s tragedy in local contexts. Their relevance for providing GPGs followed from elucidating the pivotality of the weakest-link player in providing certain GPGs, such as disease eradication. Examining aggregate-effort GPGs then yielded the conclusion that Hardin’s tragedy becomes particularly important when the provision of GPGs depends on the sum of all countries’ efforts. Thus, Ostrom’s principles scale up to the extent that GPGs have a weakest-link structure, while they give little guidance when dealing with aggregate-effort GPGs, such as climate change mitigation.

References

Barrett, Scott. 2007. Why Cooperate?: The Incentive to Supply Global Public Goods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2016. ‘Coordination vs. Voluntarism and Enforcement in Sustaining International Environmental Cooperation’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(51): 14515–22.

Bueno de Mesquita, Ethan. 2016. Political Economy for Public Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dattani, Saloni. 2020. ‘The Story of Viktor Zhdanov - Works in Progress’. Works in Progress. https://worksinprogress.co/issue/the-story-of-viktor-zhdanov (September 8, 2023).

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. Science 162(3859): 1243–48.

Harstad, Bård. 2023. ‘Pledge-and-Review Bargaining’. Journal of Economic Theory 207: 105574.

Henderson, D. A. 1987. ‘Principles and Lessons from the Smallpox Eradication Programme*’. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 65(4): 535–46.

Hindmoor, Andrew, and Brad Taylor. 2015. Rational Choice. 2nd edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Keohane, Robert O., and Michael Oppenheimer. 2016. ‘Paris: Beyond the Climate Dead End through Pledge and Review?’ Politics and Governance 4(3): 142–51.

McGinnis, Michael, and Elinor Ostrom. 2008. ‘Will Lessons from Small-Scale Social Dilemmas Scale Up?’ In New Issues and Paradigms in Research on Social Dilemmas, eds. Anders Biel, Daniel Eek, Tommy Gärling, and Mathias Gustafsson. Boston, MA: Springer US, 189–211.

Ostrom, Elinor et al. 1999. ‘Revisiting the Commons: Local Lessons, Global Challenges’. Science 284(5412): 278–82.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 2015. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Reissue Edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, Elinor, James Walker, and Roy Gardner. 1992. ‘Covenants with and without a Sword: Self-Governance Is Possible’. American Political Science Review 86(2): 404–17.

Schmidt, Averell. ‘Damaged Relations: How Treaty Withdrawal Impacts International Cooperation’. American Journal of Political Science Forthcoming.

Tadelis, Steven. Game Theory: An Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom’s focus on conditional cooperation is theoretically underpinned by the literature on (infinitely) repeated games. For instance, the ‘folk theorems’ of repeated games show that, with sufficiently low discount rates, any feasible outcome can be supported as a subgame-perfect equilibrium (Tadelis 2013, 211).

See Hirshleifer (1983, fig. 3) for a formal analysis of the divergence between the efficient amount of public good provision and the amount provided in the Nash equilibrium, and how that divergence changes as the number of players increases.